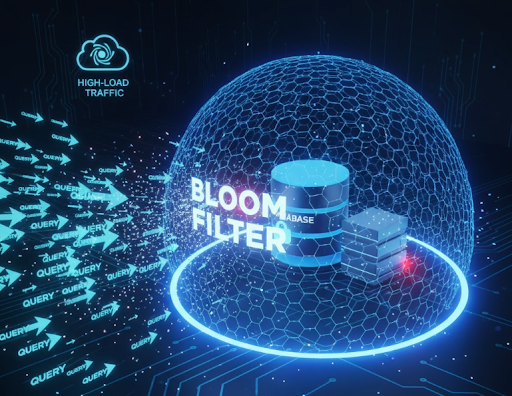

The challenges

Before diving into the solution, it’s crucial to understand the high-load, high-volume scenarios that challenge modern distributed systems. The following scenarios illustrate common “boolean-checking” bottlenecks. Feel free to read a few of these scenarios and skip ahead if you recognize the pattern.

Checking for Banned Users, Spam Content, and Email Blacklists

Assume a system where every incoming request, action, or email must be validated to determine: “Is the originating user banned?”, “Is the content known spam?”, or “Is the email address/sender domain on a blacklist?” Doing a synchronous lookup in a primary database or even a shared cache for every single action (login, comment, email receipt) creates a massive, unnecessary read load, diverting resources that could be used for core business logic before even initiating deeper, resource-intensive processing.

Cache Miss in Distributed Caching Layer

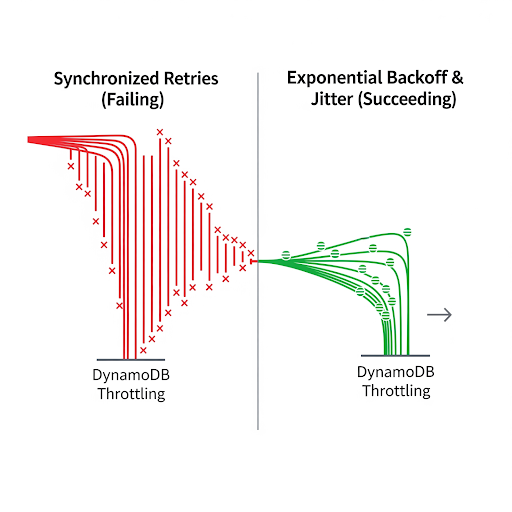

In a large distributed system, a common pattern is to have a caching layer (like Redis) in front of the database. However, when a system encounters the thundering herd 🔗 problem — many requests for the same missing key after the cache has expired or evicted it — all those requests hit the database simultaneously, leading to debilitating cache-miss storms and slow service response times.

Recommendation System History Checks

When generating a list of recommendations, a service needs to ensure the user hasn’t already suggested, viewed, or explicitly dismissed each item. This involves a one-to-many check — the recommendation list size multiplies the necessary history lookups with the core question “Has the user already interacted with this item?” leads to many requests per single recommendation endpoint call.

Session Revocation & “Logout from All Devices”

To instantly invalidate a user’s session across potentially dozens of active devices, a system must flag a session ID as revoked. The core question for every subsequent request is: “Is this session ID revoked?” Constantly querying a definitive session store for every request from every user to confirm a negative state (i.e., not revoked) creates an immense, latency-sensitive read burden.

De-duplication in Data Pipelines (e.g., Logging/Analytics)

Data processing pipelines, especially for real-time logging or analytics, must quickly check if a new data record has already been processed to prevent duplicates. This “is it present already?” check is required for every single item in the high-velocity data stream.

Notice the critical pattern emerging across all these challenges: the problem is not about complex computation or large data writes. It is a sheer volume of simple, high-frequency read requests that only require a binary answer of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (Exist’s or doesn’t exist? Banned or allowed? Present or absent? Flagged or unflagged?). The read traffic generated by these simple checks from internal and external high-volume sources is overwhelmingly high compared to the actual writes or complex transactions, crippling system performance and scalability.

The Solution Idea: The Guessing algorithm

The core challenge behind all these cases is that our systems spend enormous time and resources answering one very small question: “Does this exist?” or “Is this valid?” Each of those checks — whether for a history, a banned user, or a spam pattern — costs a round trip to a database or a distributed cache. When millions of requests flood in, those small questions become the most expensive part of the system.

But what if we didn’t have to ask the database or cache every time?

What if we had a lightweight, local data structure that could guess the answer, and be right almost all the time — especially when the answer is “no”? For the systems where the negative case dominates overwhelmingly and if we can confidently say ‘no’ then we could skip 99% of those queries, the payoff is massive. For example, in the case where we’re checking “is this user logged out already?” for every single request; a correctly predicted ‘no’ answer can reduce at least 99% traffic as most of the users usually would be logged in when trying to access authorized content.

This is where our probabilistic algorithms enter. The algorithm doesn’t try to know everything — it only needs to be certain when something doesn’t exist and uncertain when it might.

This fast, local algorithm provides two simple outcomes:

“NO” (The Guaranteed Negative): This answer is 100% certain the item is not in the set (e.g., user is definitively not banned). This result is trusted instantly, and no expensive check is required.

“MAYBE” (The Probabilistic Positive): This answer means the item might be present, but it carries a small risk of error (false positive). If we get “Maybe,” we are forced to execute the slow, definitive check against the database to confirm.

As we’ll be using it in a place where a ‘no’ is dominating response, it’ll reduce the traffic insanely. Let’s see it, not just talk about it.

The Bloom Filter — Visualization Before Code

A Bloom Filter is basically a fixed-length bit array, all bits initialized to zero. Then it uses multiple hash functions to map input values to positions in that array.

Step 1: The Empty Filter

Suppose we have a Bloom Filter of size m = 10 bits and k = 3 hash functions. At the beginning, everything is zero:

Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Bit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Step 2: Adding an Element

Let’s insert “user_123”. We run it through 3 hash functions, each returning a position within 0–9 range (mod 10). Note that here we’re just using some random numbers as return value from the hash functions for the demonstration and note that when implementing the hash functions we must ensure that the same hash function always returns the same value for a particular input, just like other traditional hashing algorithms.

hash_algo_1(“user_123”) → returns 3

hash_algo_2(“user_123”) → returns 7

hash_algo_3(“user_123”) → returns 9

We set bits 3, 7, and 9 to 1.

Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Bit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Step 3: Adding Another Element

Now insert “user_999”.

hash_algo_1(“user_999”) → returns 9

hash_algo_2(“user_999”) → returns 7

hash_algo_3(“user_999”) → returns 4

We set bits 9, 7, and 4 to 1. But as some of these bits are already 1, we’ll only set the new one 4 to 1.

Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Bit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Step 4: Querying — the best part

Let’s check whether user_100 exists.

hash_algo_1(“user_100”) → returns 4

hash_algo_2(“user_100”) → returns 3

hash_algo_3(“user_100”) → returns 8

4 and 3 are 1, but 8 is set as 0 in the array, so we can strongly say that we’ve never got an input that had hash values [4, 3 and 8]. So, user_100 DOES NOT EXIST.

Now, what about user_999? Our hash functions will return [9, 7 and 4]. Look! Those are all 1. So we can say YES THEY EXIST! Actually not. We can strongly say “DO NOT EXIST” but can’t surely say “YES THEY EXIST”.

Here is how — Both of our user_123 and user_999 have contributed to setting some of the same bits in the array — bit 7 and bit 4 in particular.

When we now check for a third user, say user_555, and its hash functions coincidentally point to those exact same bit positions, all those bits will already be 1 — not because user_555 was inserted, but because previous insertions flipped them while adding unrelated users. So the Bloom filter says “maybe it exists,” but it’s fooled by the overlapping bit positions. This is what’s known as a false positive. And in these cases we actually have to hit the storage whether it’s a DB or Cache to make sure and change the answer from ‘maybe’ to ‘yes’.

Here is a pseudo code that demonstrates a straight forward implementation. Note that, the following code is for learning practice, real-world Bloom filters often use more careful hash function selection and bit manipulation with fine grained control over false positive ration, scaling up, efficient hashing and rehashing techniques.

// Data structure to hold the Bloom Filter

class BloomFilter {

bit_array: array<bool>

num_hashes: int

size: int

// Constructor

BloomFilter(int size, int num_hashes)

this.size = size

this.num_hashes = num_hashes

this.bit_array = [false] * size

end

// Hash function generator (conceptual)

// For simplicity, assume we can derive k different hash outputs deterministically

private int[] get_hashes(string item)

// Return k integer positions between 0 and size-1

return [hash(item + i) mod size for i in 1..num_hashes]

end

// Insert an element

void add(string item)

positions = get_hashes(item)

for pos in positions

bit_array[pos] = true

end

end

// Check membership

bool ifExist(string item)

positions = get_hashes(item)

for pos in positions

if bit_array[pos] == false

return false // Definitely not present

end

end

return true // Maybe present

end

}

The Probability Magic

Let’s add a bit of math so the logic is clear.

Let:

m = number of bits in the Bloom filter

n = number of inserted items

k = number of hash functions

After inserting n items, the probability that a given bit is still 0 is:

p = (1 – 1/m)^(kn)

So, the probability that a bit is 1 is:

1 – p = 1 – (1 – 1/m)^(k * n)

Now, the probability of a false positive (meaning all k bits are 1 for an element that wasn’t actually inserted) is:

f = (1 – p)^k = (1 – (1 – 1/m)^(k * n))^k

The control & The cost

From the above maths, you can now see how the false positive rate (f) increases as more elements are added. For example:

m (bits) | n (items) | k (hashes) | False Positive Rate |

10,000 | 1,000 | 7 | ~1% |

10,000 | 2,000 | 7 | ~3% |

10,000 | 5,000 | 7 | ~20% |

As more elements are inserted, more bits are set to 1. The filter slowly saturates, and its accuracy drops because more lookups end up with all bits set to 1, increasing the false positive chance.

The less the false positive is, the better our guessing will become which results in less call to the application we’re protecting. To control that ratio, we can resize the bit array. A larger array means fewer collisions and a lower false positive rate. Let’s take an example for one million (1,000,000) items with five hash functions (k = 5) and calculate how large the array (m) needs to be to maintain different accuracy levels.

Target correctness | False positive rate (f) | Required bits (m) | Approx. memory (bytes) | Memory per item (bytes) |

90% correct | 0.10 | 5,017,000 | 627,125 | 0.63 |

99% correct | 0.01 | 9,850,000 | 1,231,250 | 1.23 |

99.9% correct | 0.001 | 17,286,000 | 2,160,750 | 2.16 |

99.999% correct | 0.00001 | 47,457,000 | 5,932,125 | 5.93 |

So for a million items, a Bloom filter tuned for 99.9% accuracy (that’s only 0.1% false positives) needs around 2.16 MB of memory. That’s microscopic in modern terms — barely a few pixels of a JPEG. Yet it can block 999,000 out of every 1,000,000 negative lookups locally, letting only about 1,000 requests reach the database.

In other words, for the cost of just a couple of megabytes of RAM, the system avoids nearly a million expensive round trips to storage. That’s the kind of trade every engineer dreams of!

Conclusion

Bloom filters have become an indispensable tool in modern distributed systems where speed and efficiency matter more than absolute certainty. By quickly filtering out negative cases locally, they prevent millions of unnecessary database or cache hits, letting systems focus on the requests that truly need attention. Today, they are widely used in high-scale services like Google Bigtable, Apache HBase, Apache Cassandra, and Redis, as well as in web applications for spam detection, recommendation engines, and session management.

In essence, Bloom filters turn overwhelming read traffic into a manageable trickle, providing huge performance gains for minimal memory cost. A few bits can save millions of trips to storage — Minimal memory, maximal effect! Bloom filters are real engineering magic.